Reviewed and Updated: July 31, 2024

BMD or bone mineral density is a marker that’s discussed in the context of bone health, osteoporosis and fracture risk. But does it tell the whole story of bone health? Maybe not. Bone quality might paint a more complete picture. Let’s discuss what it is and why it’s useful for understanding your bone health.

What is Bone Density?

Bone density or bone mineral density (BMD) is a measure of the mineral content (primarily calcium and phosphorus) within a specific volume of bone tissue. It is the primary measure of bone health and strength particularly to determine if one has osteoporosis. Measurements of bone density are often taken at various sites in the body, such as the hip, spine, or wrist, using techniques like dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA or DEXA)

Bone density scores are expressed in grams of mineral per unit volume. Typically, it’s estimated that those with higher scores face less risk for fractures and osteoporosis and those with lower scores face greater risk.

What is Bone Quality?

The common sense is that a denser bone is a stronger bone and that it should resist fractures. But that hasn’t always proven true. That means DXA technology, which only considers a bone density (BMD) measurement, has a limited ability to determine fracture risk.

For example, one could take fluoride capsules which would result in denser bones but they would be more brittle as well. So there’s emerging usefulness to considering bone quality which takes into account a number of factors including bone density to measure bone health and strength. Factors that make up bone quality include bone turnover, bone microarchitecture, bone mineralization, bone microdamage, bone-collagen content.

American Bone Health recommends Trabecular Bone Score + DEXA Scan to evaluate bone quality.

Aspects of Bone Quality

Below we’ll discuss the definitions of the aspects of bone quality.

Bone Turnover

Bone turnover refers to the continuous process of removing old bone tissue and replacing it with new bone tissue with little change in shape that happens throughout the entirety of one’s life. The turnover has two phases called bone resorption and bone formation.

In the bone resorption phase, specialized cells called osteoclasts break down and remove old or damaged bone tissue. This process releases calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and products of collagen into the extracellular fluid within the bone microenvironment, where these materials can be further utilized for bone remodeling. In the bone formation phase, other cells called osteoblasts build new bone tissue. This cycle is essential for maintaining bone health and adapting bone structure for repairing microdamage or changing biological/mechanical demands. For example, repeated stress, such as weight-bearing exercise or bone healing, results in bones thickening at the points of high stress.

Bone-Collagen Content

The collagen content of bone plays a significant role in bone quality. Collagen is the primary organic component of the bone matrix and is essential for structural integrity and flexibility. Here's how bone-collagen content is related to bone quality:

Collagen's structural role: collagen fibers make up a great deal of the bone matrix. These fibers provide tensile strength to the bone, allowing it to bend slightly without breaking. Collagen can also increase bone density and aid in bone formation.

Fracture resistance: in healthy bone, collagen forms a precise, interlocking grid that prevents cracks or microdamage from spreading. In contrast, bone with altered collagen structure or composition may be more vulnerable to fractures.

The link between collagen and bone quality is also seen in what happens as collagen degrades in quantity and quality. The aging process can result in decreased collagen quality and alterations in collagen's organization, leading to increased fracture risk.

Bone Essense provides 600 mg of Type II collagen per serving. Consider it if you’re looking for a bone and joint health supplement.

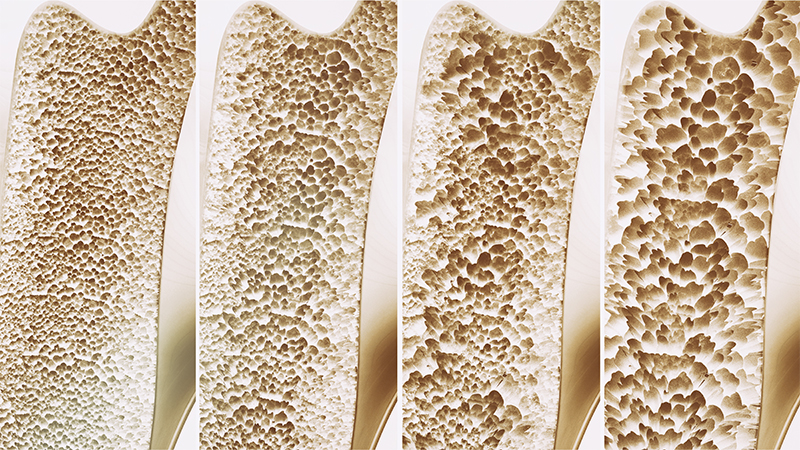

Bone Microarchitecture

Bone microarchitecture is the complex three-dimensional arrangement and organization of bone cells, mineralized matrix, and collagen fibers within bone tissue at a microscopic scale.

This structure and organization plays a significant role in determining one’s ability to resist fractures and adapt to mechanical demands. For example, bone mineral density can be increased by taking fluoride supplements. However, this also makes bones more brittle and prone to fracture highlighting the importance of composition and microarchitecture.

Bone Mineralization

Bone mineralization is the process of bone minerals being deposited in the bone remodeling cycle (primary mineralization) and further mineralization after the remodeling cycle has been completed (secondary mineralization).

The degree of secondary mineralization is dependent on bone turnover. When there is low turnover, there is more time for mineralization to proceed. On the other hand, when there is high bone turnover, recently formed bone is removed before there is time for prolonged secondary mineralization.

The degree of mineralization and its distribution throughout bone can be measured ex vivo by several methods including microradiography, quantitative back-scattered electron imaging and spectroscopic techniques.

Bone Microdamage

Bone microdamage refers to very small, often microscopic, injuries or defects that occur within the bone tissue. This damage is most often the result of repetitive mechanical stress, such as from normal daily activities, sports, or other physical impacts on the skeletal system.

There are two primary types of bone microdamage:

- Microcracks: tiny, hairline fractures within the bone tissue that are not usually visible under normal imaging. They can be the result of repetitive stress and are associated with the wear and tear of bones.

- Microvoids: Microvoids are small gaps or spaces within bone tissue that may result from microcracks or other factors. These voids can affect the bone's structural integrity and may influence its overall quality.

Individual instances of microdamage can’t tell one much about their bone strength or fragility.

Bottom Line

As of this writing, bone mineral density is still the primary clinical measurement or proxy for bone health and strength. However, it might not provide the full picture on one’s bone health or fracture risk. Bone quality might provide a clearer picture of one’s bone health. Clinical practice on measuring the aspects of bone quality is still an evolving area.

* This article is for informational purposes only and doesn’t constitute medical advice. For immediate health concerns, please consult your physician.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent disease.

© 2024 Best in Nature All rights reserved

Validate your login

Sign In

Create New Account